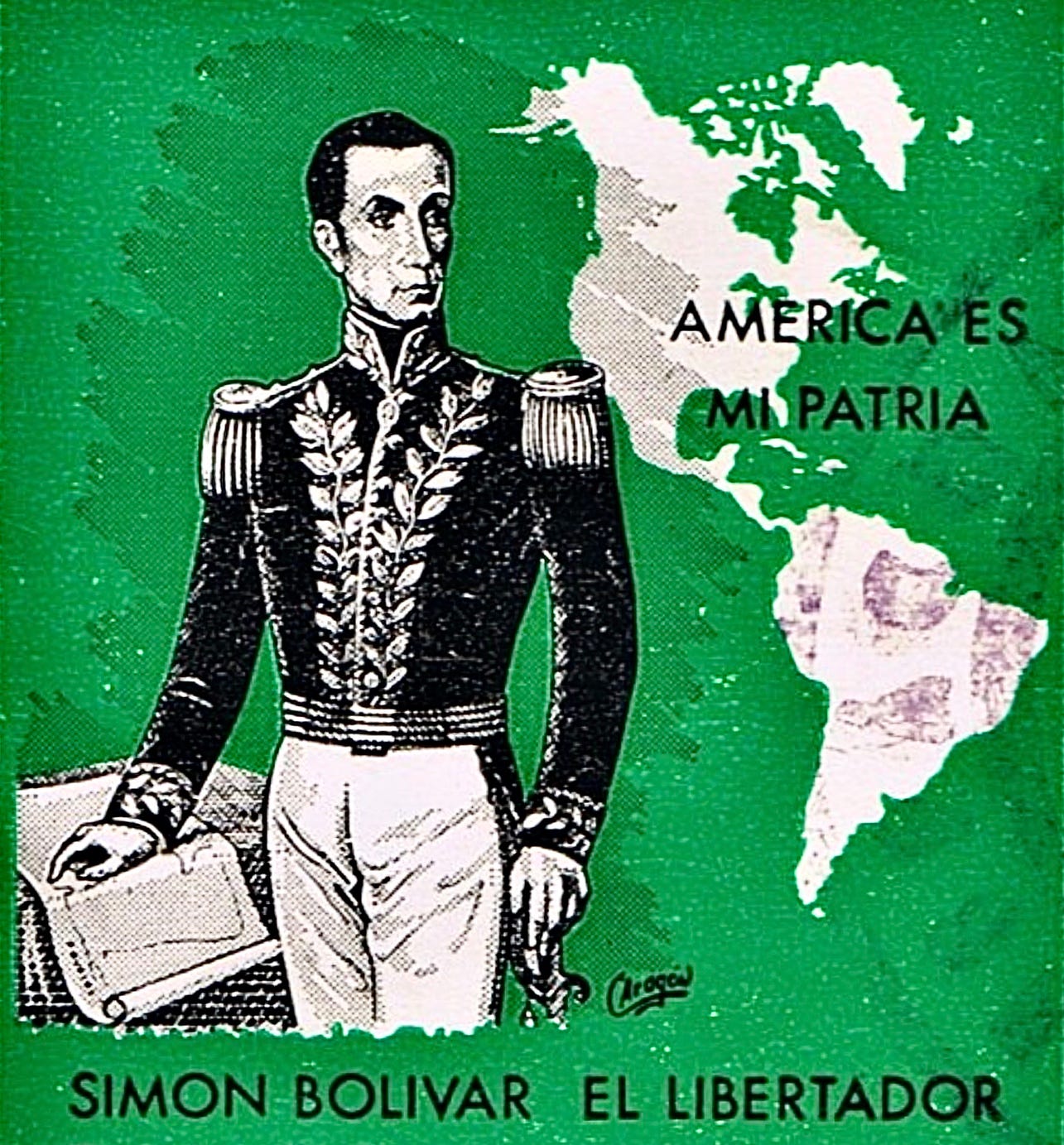

Pan-Americanism means following in Bolivar’s tradition, and upholding 1776 so we can build on its legacy

By the accounts of people who’ve created biographies of Simon Bolivar, he admired the USA’s founding fathers for their achievement. So why has Bolivar become the namesake for the foundational ideology of a great part of Latin American socialism? Why is Bolivarianism the thing that the arbiters of Venezuela’s anti-imperialist project affiliate themselves with? Because despite what many Marxists in the modern U.S. say, upholding 1776 is an essential part of being a socialist and an anti-imperialist.

It’s a crucial aspect of what gives somebody the theoretical knowledge to be able to make socialism into more than a mere concept, and actually build socialism. Doing so in this hemisphere means being pan-American, and being pan-American means seeing that the great majority of countries in the Americas don’t need to be abolished. With some exceptions, which I’ll get into, these countries only need to be sublated into being workers states.

Understanding that Bolivar, Marx, Lenin, and other important revolutionaries have been correct in upholding 1776 is so important because it lets us answer the national and civilizational questions. It gives us the historical perspective we need in order to avoid making grave mistakes when it comes to dividing territory. Mistakes such as creating full land independence for every nation as an absolute, rather than taking the Leninist position of simply supporting the right of nations to self-determination. There’s a meaningful difference between these two things; this is the difference between what successful revolutions within the Americas have actually looked like, and the idealistic notions ultra-leftists have about what they should look like.

When Venezuela has begun its transition to socialism, this process hasn’t involved an effort to abolish Venezuela, like how the ultra-lefts I’m referring to want to abolish Mexico. And though imperialism’s propagandists accuse the Bolivarian government of oppressing indigenous people, as they do to practically every other anti-imperialist government, this path has objectively been the best one for the tribes within Venezuela and the country’s broader working masses. If Chavez had sought to abolish Venezuela, realistically he wouldn’t have come into power in the first place. And if he had been able to implement such a plan, he would have left the land even more vulnerable to imperialist counterrevolution. Splitting up a country always makes that country a weaker target for the reactionary forces, which is why Lenin and Stalin didn’t simply make every nation within the former Russian empire a fully separate entity. It’s basic practicality to not give up your gains within a war once you’ve attained them.

To apply this reasoning, we need to recognize exactly why Bolivarianism is what’s explicitly defining Venezuela’s revolution. (As well as why the other anti-imperialist Latin American governments have also not dissolved the countries they run.) It’s because a country doesn’t need to do away with every aspect of itself in order to take on a revolutionary character. At the moment when its founders defeated Britain, the United States had a revolutionary role, for the same reason that the countries Bolivar liberated from Spain had a revolutionary role. Obviously the United States doesn’t have such a role now, and it hasn’t had one arguably since the 18th century. The solution isn’t to sneer at the patriotic sentiments of the country’s people, though. It’s to nurture the people's growing anti-imperialist impulses and class consciousness. Which is a task that’s undermined when the idealists wage their symbolic cultural battles against the U.S. flag.

I don’t know if the USA will continue to exist as “the USA” following its proletarian revolution; maybe the conditions will call for its character to change in that regard, it’s too early to say for sure. The important thing is that this revolution isn’t going to need to involve immediate and total tribal independence in order to represent progress. In fact, if we were to try to do this in a literal and absolute sense, it would create the equivalent kinds of problems that Lenin and Stalin knew to avoid. It would be an impossible task, as it would mean trying to have the tribes singlehandedly govern an overwhelmingly non-Native population. It would also be in conflict with the tribal entities that the idealist radicals claim to speak for, because it would be going ahead of what wishes they’ve articulated. Within a Leninist revolution, the indigenous First Nations will get sovereignty if they wish it, and trying to implement a “decolonial” model that overrides their will would ironically be chauvinistic. We can’t speak for the tribes, only the tribes can speak for themselves.

When I shared the idealistic view of the national question, I pointed to how the tribes in eastern Oklahoma have gained stewardship over their majority-white region, which is indeed something we should take note of. But I was mistaken to have blanketly advocated for the tribes to undergo the same process throughout all of their ancestral lands; because throughout a great deal of the country, the demographics aren’t of a character that makes such a thing feasible. There are many areas where the tribes that were originally there are no longer in their original territories, and this makes them unable to undergo the same process that’s occurred for the ones in east Oklahoma. Recognizing this isn’t chauvinism, it’s just seeing reality.

Where the tribes push to regain their territory, they need to get what they desire. To promote the dogma that all the land should simply be returned to the tribes, without applying a scientific analysis to how the territory must best be distributed in each given area, is to obstruct the task of revolution. It’s to replace scientific socialism with dogmatic moralism, a moralism that’s detached from what the tribes have actually said they want.

To get an idea of what revolution on this continent is truly going to look like, look at where the forces of monopoly finance capital are arrayed, and which forces are working to defeat them. In an attempt to save their decaying imperial order, the finance capitalists have cultivated a layer of radicalism that seeks to negate history and dialectics in favor of ultra-leftism. This false opposition, and finance capital’s other counterrevolutionary tools, partly have the purpose of preserving colonialism. Which is ironic, since the bourgeois academics behind these ultra-left theories claim to be fighting colonialism. As long as “Marxism” stays in this idealistic form, and doesn’t take on a scientific socialist character, the system isn’t going to be seriously challenged. Which means that colonialism, and the other facets of capital’s rule, will remain in existence.

Among the most blatant modern examples of colonialism is Canada. Canada resembles the “Israeli” settler state more than the modern U.S. does, to the effect that it’s not nearly as able to be sublated into socialism as the U.S. is. It can actually be considered a fake country, because it hasn’t undergone the equivalent to the nation-creating process that the U.S. has.

Whereas the size and diversity of the USA’s population has let its working class develop a clear patriotic heritage within the struggle, one that U.S. communists have historically been able to use as a rallying point, Canada is severely underdeveloped in this area. As the Canadian Alex Green has observed: “Canada lacks a cohesive identity or sense of itself as anything besides ‘not the US.’ Our population is tiny, spread mostly along the southern border, and in most of the land mass — the parts claimed by ‘the crown’ and private companies, and largely inhabited by Indigenous communities that have lived there since the beginning of human memory — anything resembling state services or essential infrastructure is few and far between.”

These Native peoples within “Canada” continue to be heavily exploited and policed. And the synthetic nature of “Canada” places the tribes in conflict with the “Canadian” identity, moreso than is true for the American identity in relation to the tribes here. What we call Canada is a front for not just settler-colonial extraction, but colonial extraction of the foreign kind. This continues to be true despite the “independence” from Britain that Canada has supposedly gained. The only reason why we don’t see the UK act with outward involvement in Canadian politics is because the Canadian state doesn’t challenge the monopoly finance interests of Britain’s new empire. If a Canadian bill were to go against these interests, the King would have the authority to not provide his “assent” for it, and thereby block it. And if a Canadian prime minister were to act against these interests, the King would be able to fire them.

This represents part of the unfinished business of the American revolution. 1776 stopped the British empire from having authority over much of the continent, but we have yet to kick the crown out of North America. And this problem is fundamentally tied to all the other aspects of the class struggle, including the fight for Native liberation in both the U.S. and “Canada.”

To win the class struggle, we need to wage a serious campaign against U.S. hegemony. This is something that’s disregarded by the default ideological forces within “land back” circles, because the “land back” label is not something that comes from an indigenous mass base; the phrase has become so popular because it’s the slogan that elites have used to capture the Native liberation movement. Using its NGOs, “radical” academics, and media psyops, finance capital has diverted many developing radicals away from the resistance towards U.S. hegemony, and towards instead centering the vulgarized “land back” slogan. This has led them to focus mainly on fighting the lower levels of capital—as in the enterprises small enough to only have a domestic presence—which helps the monopolists.

International monopoly finance capital is fine with U.S. radicals focusing on fighting the petty-bourgeoisie, and on attacking patriotic symbols. Imperialism is going to remain just as strong if we embrace this mode of practice; if anything, it will get fortified by this. It helps the monopolists in their efforts to degrow the economy, and to spread a sense of nihilism among the people about their own communities and society. They want us to be dominated by thoughts like “I hate this country and everything about it,” rather than engaging in revolutionary optimism so we can connect with the people.

The latter is the mindset of the anti-monopoly coalition which has emerged since the start of the Ukraine proxy war; the communists, libertarians, and other antiwar actors in this coalition are fighting the fights that truly matter, rather than either side of the culture wars. The imperial system’s intelligence trackers have taken notice of this coalition, and have announced their desire to counter it. As a communist, this is why I’ve joined the Center for Political Innovation, which is one of the Marxist organizations within this grouping. You don’t need to join CPI or any other one org to contribute to this effort; my minimum suggestion is that you enter into this struggle in whatever ways you can, while being open to forming connections with whoever proves themselves to be a good ally in the fight against the hegemon.

We won’t win unless we confront our class enemies on an international scale, the scale at which they’re operating. If we think small, and fixate on attacking the enemies of our enemies, then we’ll continue to lose. That’s the meaning of pan-Americanism as it exists in our time. It means accounting for all the fronts in the war against monopoly capital, not just throughout the Americas but also everywhere else. Since Bolivar’s time, capitalism has developed to its highest stage in monopoly finance imperialism, so his pan-American vision can now only be fulfilled by orienting ourselves against this system. We will unite workers of all colors, and all the allies they can find, in their fight against monopoly power. Then when we’ve overthrown our monopoly capitalist dictatorship, we’ll do whatever is necessary to liberate the indigenous Canadians. We will build on the legacy of 1776, and defeat imperialism for all time.

————————————————————————

If you appreciate my work, I hope you become a one-time or regular donor to my Patreon account. Like most of us, I’m feeling the economic pressures amid late-stage capitalism, and I need money to keep fighting for a new system that works for all of us. Go to my Patreon here.

To keep this platform effective amid the censorship against dissenting voices, join my Telegram channel.

To my Substack subscribers: if you want to use Substack’s pledge feature to give me a donation, instead donate to my Patreon. Substack uses the payment service Stripe, which requires users to provide sensitive info that’s not safe for me to give the company.

Here is what Simon Bolivar said about the United States of America in 1829: “The United States appear to be destined by Providence to plague America with misery in the name of liberty.”

Bolivar was prophetic.

Two hundred years later, Bolivar's words can be updated to assert that the United States is destined by Providence to plague the entire world with misery in the name of liberty.

Just to add to my precious comment, I want to say that if Bolivarians supported the American “Revolution”, it is because they were misinformed about its character. And that’s completely fine. Movements, historical figures and states can be wrong sometimes, which is why I support none of them uncritically.

When, as a Marxist, you read something like that, your alarm bells should be ringing. You should recognize it as an L on the part of Bolivarianism. Take the good with the bad. I admire the movement for its achievements, but this was clearly a mistake on their part.

Vietnam made the same mistake, with a key difference. Ho Chi Minh was in fact very inspired by America’s Declaration of Independence. So much so that he reached out to the Americans for help with Vietnam’s revolution, having seen how the founding fathers claimed to support “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness”.

Needless to say, the U.S. responded by giving military support to France, their colonizer.

Herein lies the difference. Ho Chi Minh immediately changed his mind about the United States, and when Americans came to invade his homeland, he fought back against them and won.

Stalin, too, was wrong about certain things. He used to support Israel, thinking that it had the potential to become socialist at a certain point. He, too, ended up changing his mind later on, even when others in the Communist Party remained misled about Zionism.

If most Marxist were to do what you have done with this post and take his initial support of Israel at face value, saying “look, Stalin supported Israel, we should too”, then we’d be just as reprehensible as fascists.

Additionally, I think comparing the Soviet Union not wanting to balkanize its republics to decolonization in America is pretty nonsensical. They aren’t related at all. The origins of the Russian state can be traced back to the establishment of the Rus’ state in 862 CE.

The average Russian can trace their ancestry back to 15 generations and still find that they lived in the same place. Most Euro-Americans can barely trace their ancestry back 3 generations before the genealogical record inevitably leads them to the British Isles or Germany.

The American “Revolution” is widely regarded by MLs as a bourgeois revolution, but I’d go so far as to contest the idea that it was a revolution at all. Sure it was a conflict between different capitalists, but it did nothing to fundamentally change the structure of society. It simply changed which slave-owning settlers controlled the capitalist state.

You could argue that North America was still feudal in 1776, but that’s another discussion. I personally think it was a mix of both modes of production.

Lastly, Canada, for the very same reasons, is just as synthetic of a nation as the United States. The primary difference between the two is that the latter developed a stronger sense of bourgeois nationalism, while the former never did due to remaining within the British sphere of influence.

Another difference is that, if it can be said that the United States has almost entirely completed its settler colonial project, Canada is still carrying out its own.

The Indigenous population in Canada hovers around 5%, compared to the American 1%. Canadian police carry out crimes against First Nations people more openly for this very reason.

Their society also seems to be more viciously racist against the Indigenous population, partly as a result of having more regular contact with them, unlike in the States where most Americans will never visit a reservation. The most exposure they’ll get to their idea of Indigenous people is through Hollywood depictions or commodities.